The Imperial chambers are central in the Marble Palace. That night after dark, I went by myself to one of the offices that had a bay window with a cushioned sill, overlooking the city.

It was an overcast night, the only light that of people: street-lamps, brass torches carried by walkers, the orange glow and blue flicker of a brazier, a F’talezonian stained-glass light-globe of green, purple and gold in some Aitzas’s parlour. I swung open the panes, and the night sounds of Arko came to my ears on the still air, same as always: talk, footsteps, the creak of a carrying chair, a harper singing, the melodious burst of a woman’s laugh.

I listened, and thought, “All over this city people are saying to each other, ‘Chevenga has always thought he’d die before thirty.’ ” Perhaps some of the conversations I was hearing, too distant to make out, were about that. The thing that for three quarters of my life I had schooled my mind and body and soul against letting slip by word or expression, the thing with which I had locked myself inside inward stone walls, alone with my ruined dreams, my accommodation strategies, my secret strictures, my shock, my anger, my haggling, my sorrow, my shame, my fear and my hard-won peace, for twenty-one years, was being kicked about over a thousand dinner tables, passed down a hundred streets, distorted to as many versions as there were people telling it. And tomorrow morning I would confirm it officially and give the correct version, banishing entirely the one thing that still protected me: disbelief.

I started trembling, then weeping; I tried to do the twenty-years-in-the-future chiravesa again, but the emotion was too strong, overcoming me like a fever. Afraid for myself, I called a servant to walk me to the clinic. Kaninjer’s medicines again let me sleep. I dreamed I had a tap hammered into me through the wound as if I were a maple tree, and my life-blood was running out into buckets, from which a crowd was tasting it, and judging it like wine. “Ah, a little rich in the foretaste, mellow, yet audacious.” — “Yes, there is boldness there, and an admirable aspiration to refinement, but a rough edge.” And one—of course—shook his head sadly and said, “Alas, this would have been brilliant, with longer aging.”

In the morning I partook of both Haian medicines and un-Haian ones, to get myself telling the writers. The water in my water-flask was half wadiki. Call me a coward: I wanted to feel little or nothing of what I was saying, to be distanced from it as if I were watching from afar. If anyone noticed, they were kind enough not to comment. When I sat at the table Krero and Surya took up positions close on either side of me, like bodyguards.

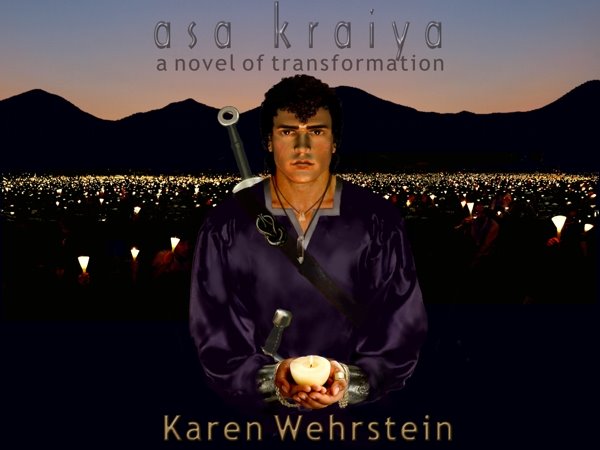

Like Intharas, most of the writers had been expecting a firm denial, and were stunned. I told it as I had told it to Idiesas, Krero, Tyirian and Kaninjer, about having thought it was foreknowledge all my life, but now was undergoing healing to overcome it. (Beforehand, I’d proposed to Surya that I introduce him to them, since that would probably fill his practice to bursting, but for some reason he would have none of it.) I answered questions until they had no more. I did not say that I would go asa kraiya, wanting to keep something for my own people to hear first. The writers fairly ran out the door, to give my secret to the world.

Minis had attended in his Minakis-guise, fitting right in. He seemed less astonished, when we spoke afterwards, than I expected. “That’s what my father meant in his letter, wasn’t it,” he said, “when he wrote ‘Don’t worry about Chevenga, time will take care of him’?” I had gathered Kurkas had never told him in full, but had never known he’d told him obliquely.

“You have to do what you have to do,” he said, when I apologized for delaying the announcement of his candidacy again, this time for the trip home. “They are your people, we are not.” But he could not be pleased; it would cut down his time to speak to his people by five days at the very least.

In the administrative wing, they tried not to make it obvious, of course, but the bureaucrats and clerks in the offices, the guards at their posts, the messengers in the corridors, all looked at me too long, or looked away from me too deliberately, or stared when I was turned away, thinking I could not feel it like the heat of a fire on the back of my neck. Plain in their eyes, even as they spoke of our everyday business, was the confusion, the pain, the sympathy they did not know whether or not to show, the shock.

It bothered me less when they did say something. Nyatandra Kichere, the bookkeeper who had always been a sort of mother hen among the bureaucrats, caught me in a bone-crushing hug, and said, “Thirty! Thirty! Kahara help us, Fourth Chevenga Shae-Arano-e, you deserve to live to be a hundred! You listen to me! You listen to your healer! And you make good and sure we don’t lose you for a long time, precious boy, do you hear? The world needs you, so make good and sure!” She wouldn’t let go until I promised. Others were more tentative.

“Imperator… before you go…” Anamas Karlen asked me casually into the Officiate’s main meeting room. Everyone was gathered, crowding against the walls. With a bit of a speech, Binchera handed me a gold-wrapped package. The letter with it read, “It is our dearest wish that you should have occasion to use these,” and was signed by the entire Marble Palace administrative staff, Yeolis and Arkans alike. I opened the package, and found a gold-handled walking stick, a fine pair of eyeglasses, and a Vae Arahini marya with the collar an elder wears. Though my mind was not really there, I put them on and did my best impression of myself as an old codger, to make them all laugh.

The Press is running, I thought, imagining the headline, however it would be worded, running through the machinery thousands of times over, to be shipped shipped and carted and flown to every corner of the empire and the world. I hadn’t even eaten yet; I’d fling something down while I was putting on the flying leathers, I decided. But then one of the Palace messengers came to me with a note he said was urgent. It was from Marnas Iisen, begging me to meet with him.

Marnas was the leader of the Enlightened Followers, or, in full, if you must: the Temple of the Enlightened Followers of the Deity on Earth Shefen-kas. I’d tried to have as little to do with them as possible, their very existence making me itch, but as freedom of religion was now the law in Arko, I couldn’t outlaw them.

Despite all that, though I couldn’t put my finger on exactly why, I felt refusing Marnas would somehow be impolitic, so I sent the messenger up the lesser Marble Palace lefaetas to tell the wingers on cliff’s edge they’d have to wait a little longer.

Though I’m sure many would find this hard to imagine of me, or anyone, approaching someone who worships him and would do anything he asked, I felt a knot of fear in my stomach as I went to the Jade Reclining Room to meet him. What would it be—histrionics like Freni-Raikas’s after the publication of Life is Everything? Would Marnas fling himself all over me? Beg me to save his movement? Give me some impossibly valuable thing, a bribe to stay alive? I couldn’t imagine. The old strategic saying is true, the moves of the religious are the hardest to anticipate.

When I came in, he did the prostration with the extra fillip the Followers add to it, the Arkan prayer-sign of cupped hands on the temples. Marnas was then in his fifties, I think, a tall bony old Aitzas, grave of face and bearing. He did not do any of the things I’d feared, and even kept his face emotionless in the Arkan way. He just said, “Imperator and Master, when the last of the sunset has faded from the sky tonight, there will be a gathering in the square. May we beg of you to grace us with your presence, on the Balcony of Presentation? And may I attend you?”

They’ve decided I should have become a sacred martyr after all, I thought, and plan to bristle-brush me with arrows. I told myself not to be silly. His people planned to gather in the same spirit as the administrative staff had; whatever I felt about them, they felt close to me, and wished to let me know their hearts. I got that feeling again, that I should not say no, or even postpone it, even though it meant we wouldn’t fly until the next morning. If the land winds were better than the sea winds, there was still a chance of beating the Pages to Vae Arahi. I sent up to the cliff edge again, telling the wingers we were holding off until morning.

While an indignant Krero ran around making the security arrangements he felt necessary, I worked in an office with a window. When the sky was entirely dark, I went out to the balcony. It seemed everyone else was making more of a fuss of this than I thought warranted; Niku, Skorsas, Kallijas, my mother and the children all fell into step with me, as did Kaninjer, Krero, Sachara, Surya (whom someone had sent for), Minis in his Minakis-guise and too many other friends to fit on the balcony. Marnas was already there, shining golden in his full robes and headdress as the Followers’ Fenjitzas; in my everyday white-and-gold Imperial suit, I saw, I was going to fade next to him. But the Imperial robe didn’t seem right either; this was personal, not official.

I stepped to the rail. The noise from below seemed more massive than could come from the size of crowd the Followers could raise. My ears told me right; the square was jammed. There were fifty thousand people here.

I glanced at Marnas. He said, “Master, it isn’t just us. Others thought well of our plan.”

“Plan?” I wondered if Krero knew it. Marnas did not answer, but turned to the crowd, raising his hands, one of which held a long candle. The people went quiet. He had already spoken to them, I could tell; I had come in in the middle of this, whatever it was.

Someone behind us handed him a lit taper, which he touched to the wick of the candle. Once the flame had risen to a steady height, he lifted it to the crowd. They did not cheer, as I thought they might; but the few lights they had, mostly walking-torches, began to multiply. It seemed everyone had a light, which he now lit from one held by his neighbour; slowly the square became a sea of light, a starfield of tiny flames, shifting and flickering with the life of the people holding them, an astonishing sight.

“Imperator and Master,” said Marnas. “Shefen-kas.” That got him my full attention; he had never called me by name before. “Let me tell you what this means. Every flame you see represents one person who feels with all his heart that you deserve to live.”

The glistening below, and everything else, began coming to me only in waves. I didn’t go quite into a full faint, but Kallijas and Niku had to hold me up by my arms. It took me a good tenth to master myself. I’d take a deep breath, and think I had it, then open my eyes and see fifty-thousand candle-flames, and fall apart all over again. I felt Kaninjer’s grip on my sword-hand wrist, fingers on the pulse-points, and saw the eagle-eyed-healer look on his face. I was only seven days recovered.

When I found it in me to stand steady, I wondered what to do. I should answer them; but words weren’t enough. Soon I saw. Everyone on the Balcony was holding a lit candle, but there were some spares. I took one, held it up to the people unlit, then touched it to Marnas’s. When it was burning well, I held it up again.

The roar of the crowd threw me back against Niku and Kall like a sea-wave. I put all my strength into keeping the candle high. “Marnas, I can’t speak to them because of the wound,” I rasped to him, through my tears and over the noise. “Speak for me. Tell them I can’t begin to say how this touches my heart, I can barely believe their love though I see it clearly and will remember it, I will carry it burned into my soul, forever…” I just let the words come, he belted them out to the crowd, and it roared back to me, for a while, while Niku and Kall held me steady, and when we were done they helped me back to the Imperial chambers.

--

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

35 - A sea of light

†

Posted by

Karen Wehrstein

at

4:37 PM

![]()

![]()