“I am from Kabiri, a village near Tinga-e. When I was a child, I could see auras a little, and I knew something of what they meant. But people thought I was imagining them, would say ‘Oh yes, those certainly are nice colours around so-and-so, what an imagination you have.’ It got fainter and fainter, and stopped altogether when I started my war-training. “We were very much a warrior family, my shadow-father a war-teacher by trade. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life as I was growing up; I didn’t like war-craft enough to follow him, and though I helped in my parents’ shop, I couldn’t see myself doing carpentry all my life either. I fought against the Lakans for three years, then married. My husband and shadow-wife did cabinetry, my wife did running for the Workfast Proclamatory, and we had children; I dedicated myself to them, and to the garden and the herd, because I still was not certain what else I wanted to do. “We were all four warriors, so that when the Arkans invaded, we were devastated; you know how it was with warrior families. My shadow-father, my mother, both of my wives and a good half my in-laws all got killed within three moons. Anchera and I had the children cared for and wet-nursed by someone up in the mountains who wasn’t even family, so we could fight. “When it turned around and we started winning, all was well for a while, but then I started getting sick. It was just aches and pains and nausea at first, but it worsened as we fought through Yeola-e and then into Arko. I started feeling tired all the time, depressed, I’d get fits of panic, nightmares, and catch every little thing that was going around. We thought it was grief from bereavement—but releasing my grief, crying out my heart many times, did not touch it. I went to one army healer after another, Haians, Yeolis, even an Enchian, and none of them could do anything. The Haian remedies would work for a short time, then I’d be back to where I had been before. The Haians told me it was because I was a warrior and I should quit—but you know Haians, they always say that. After everything, I was hardly not going to see it through to the end. “The only person who really helped was a Yeoli war-master. He told me that I shouldn’t worry, that the reason for it all would come clear... that I didn’t have, and this is exactly how he put it, a case of sickness, but a case of change. What that meant, I hadn’t a clue, and I guess he didn’t explain because at that time I could not possibly have understood. But he said that I shouldn’t worry with such conviction and firmness that I believed him, and that helped. “At Porfirias I had to drag myself onto the field. They were nothing but old men and boys and cripples, all that Arko had left. They’d stopped fighting, we were just slaughtering them as they ran, when I came to a point where something in me would not be denied. I couldn’t do this for a moment longer. I said so to Anchera, and threw down my sword. And then...” Surya paused, gazing off over my shoulder, his face full of the memory, which seemed both wondrous and horrific. “My gift came up, full-blown.” “Full-blown?” I asked him. “You mean—all of a sudden you were seeing everyone’s auras?” He signed chalk. “Sakra Mahaiyana... the wounded, the dying...? That must have been... I can’t imagine.” “It was as if the land was burning, a sheet of flame of agony and anguish and rage... I fell to the ground and curled up into a ball. Anchera thought I’d taken an arrow. He and someone else carried me to the infirmary. The Haians figured it out fairly quickly, when I started telling them about things that had happened to them as children. There was a man across from me who was refusing painkiller, though he was in agony. I kept wanting to scream, ‘Force it down his throat!’ So, they knew what it was, but not what to do. I felt the only person who’d have a clue was that war-master. Anchera, bless his soul, went out and found him. Azaila—that was his name—” “Azaila! Azaila Shae-Chila, of the School of the Sword in Vae Arahi?” “Yes... well, I guess you would know him.” “He was my war-teacher.” Surya laughed, and said, “Ah, I should have known it.” His eyes took on the aura-seeing gaze. “Oh yes, there he is! I see the spirit of his teaching in you.” “What does his aura look like?” “Oh, it is very beautiful, very strong, the colours all like jewels, everything integrated and well-formed, nothing out of harmony. It is a wonder to see.” “Not like mine.” Surya smiled. “Give yourself as many years as he has had, to learn and grow.” Having shut me up thoroughly, he went on. “Azaila and Anchera took me out into a forest near there, far away from the camp or the killing-field or any other people. There, he ran me through the asa kraiya ceremony.” “Azaila does that?” “Of course—he’s a war-teacher.” He shook his head, and a smile quirked the corner of his mouth. “You kraiyaseyel don’t know anything.” “You know, Surya Chaelaecha,” I said, “I’ve never had anyone make me feel as much of an ignoramus as you since I came of age.” “You’re welcome. It’s a healer’s calling to serve. Azaila, your war-teacher...” I’d already learned to fear Surya’s scheming look. “Did he give you your wristlets?” I signed chalk. “So you must be quite worried what he will think of you going asa kraiya. I have your next order. Do you know if he is in Arko, still, or back at the School?” “Back at the School. I wish he were here.” “You can’t speak to him, then—so: you will write him. Ask him his opinion of your doing this.” I took a deep breath and said, “A-e, kras’.” “No later than tomorrow.” “I hear and obey.” “Good. So anyway, he took me through the ceremony. Not that it was my true moment of laying down the sword; that had been when I had thrown it down, literally. But the ceremony formalizes it. And celebrates it. And then he suggested that I go to Haiu Menshir to be trained in how to use my gift. We had to smuggle ourselves onto the island because it was occupied by Arko then, but we managed; I got help from the semanakraseye, a letter for our privateers.” It almost slipped by; I had to let it echo again through my ears. I got help from the semanakraseye, a letter for our privateers. I froze, shivers spreading outward from my heart, sending prickles flowering all down my arms and legs. All through, Surya had never addressed me by name or by title, except kraiyaseye. I had thought it was to show me that my position was not important. Now I saw—it was that he didn’t know who I was. No—he knew better than anyone who I was. He did not know my name. “The semanakraseye,” I said wonderingly. “Yes—Chevenga himself,” he said, with a slight but unmistakable pleasure in dropping my name. “I guess it had to go that high, it was going to be tricky.” When I thought back, I could vaguely remember it coming across my desk, after Porfirias, vaguely recall scribing and signing a note to my privateers, to get a warrior secret passage to Haiu Menshir to train a gift that had incapacitated him. I played it out in my mind. The first session, he’d started saying things that shocked me so fast I’d forgotten to introduce myself. When he never asked, I had come to assume he knew by my face or the seals or the signet or the brand-marks, or Megidan telling him, which I knew now she hadn’t. But then how had he missed the clues all over me? They are surface things, I thought. He doesn’t look at the surface, at what I make myself appear to be; he looks at the centre, the truth, at what I really am. Surya looked at me puzzled; of course whatever I felt showed plain as light to his eyes. I opened my mouth to tell him the truth and apologize for not doing so earlier, and felt my tongue lock. Something in me did not want to; asking myself, I saw right away what. Not knowing my name, he knew me, not it and everything associated with it in his mind, whatever that was. To him, I was just myself, not Fourth Chevenga, conqueror of Arko, Invincible, Beloved, Imperator, Son of the Sun, and so on. I wanted to stay that way to him so badly it almost hurt. So I shrugged, and said, “Just a thought—one that’s best to tell you later, I think.” As if he’s going to let that go, I thought lamely. To my amazement, he did, and went on with his story. I felt like the child who walks onto the wrestling ground against the giant, and pulls off a victory. “Anchera saw me settled on Haiu Menshir, and then went back home to reclaim the kids, since the war was over. I studied there for two years, then went back home, and I have been practicing ever since. My Haian master gave me the name ‘Kinamun,’ which means ‘certainty.’ I’ve just translated it to Yeoli.” I could see why he’d been given that name. “Now I understood, I had not known what I wanted to do with my life because my best talent had been hidden from me. I was practicing in Tinga-e until about a month ago, when All-Spirit told me that I should come here, for some reason. Anchera and Janinara-e—my new shadow-wife—and the children were not pleased; but I had to come.” Surya lifted his teacup for a sip, and said, “Now it looks to me like the reason was to save your life.” “Surya, you are extraordinary,” I said, “and all who come to you are blessed, that in the way of All-Spirit you were given such a gift. I should not waste it.” He shook his head. “That’s it—enough rest, nose to the grindstone again. Do you hear what you are saying? You should not waste my gift, as if that is the crucial consideration in whether you live or die. Before it was Yeola-e would lose you as a warrior, as if you losing you was of no consequence at all. I do have my work cut out for me, don’t I, having to convince you your life is worth anything, for its own sake?” I couldn’t speak. I had said those words, there was no taking them back, no pretending that meaning was not in them. --

Friday, March 20, 2009

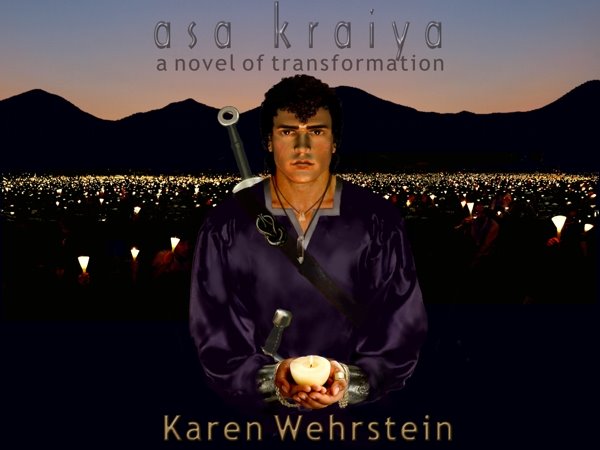

8 - Surya's story

Posted by

Karen Wehrstein

at

8:29 PM

![]()

![]()