It was a little after my third visit to Surya that everyone on the training-ground found themselves noticing Niku. “Your wife,” Kyirya Sencheli said to me, brushing dust off the back of his kilt, “is fast today.” The Niah unarmed fighting style, no surprise, has drawn all manner of wisdom from the motions of flying, especially to do with balance and leverage and strikes from high one-foot stances; there is a tricky move to down an opponent called ‘pulling over the cliff’ which relies on speed. Niku could rarely do it to Kyirya and almost never to me, but today she’d done it handily to him every time she’d tried.

She had a certain glow on her, too; between that and the greater speed I should have known, except that my heart was at least half shielding itself from knowing. “What do you mean, what’s up?” she said on the next change of partners, when I asked her. “Aba.”

I took a deep breath. Everyone else took how close we were standing to each other as meaning we were partnered, so we were. Her hands were like lightning; just as I was goading myself faster to match, she pulled me over the cliff. “You’re definitely with child,” I said, from the dust.

If only there were only joy in it, I thought. Not this icy pin-knife of pain and fear at its core. I couldn’t imagine she wasn’t feeling it worse than I, but she was not showing it. Once I was back on my feet she kissed me, and Tyirian, who was calling, barked “Chevenga and Niku, you can do that in bed!” much to everyone else’s mirth. But afterwards when they didn’t have their minds full of move and countermove, and so put two and two together, they came with hugs and words of blessing, mostly “Strength.” They remembered what it had been for us last time.

In the first and darker days of Yeola-e, everyone did the stream-test in the way that is now called the severe way. Every newborn was blue when he was pulled out of the ice-water, and about one in four never gained back his pinkness, his tiny life snuffed by the cold. Among those families who still do it, no one does it straight out of the womb any more, but leaves it until the baby is two days old, and many do barely a dip in and out, a formality.

But the semanakraseyesin is in that way, like many others, old-fashioned. I and my father and my grandmother and every Shae-Arano-e ancestor before me was left in for the full run of the stream-testing monk’s sand-timer. Niku had agreed to it even before we married, and honoured it even with Vriah, our first, though neither I nor the monks were anywhere near Ibresi, where she was born, and Niku was not even entirely certain I was alive.

Then, fairly soon after the sack—so, during my first term as Imperator—we conceived again. I had not known there were twins in her family; she told me after the midwife felt two children within when she was about seven months along. “If they’re both boys, omores, we needn’t argue over which of our fathers to name our first son after,” she said, with that smile with a kind of shining in it that only pregnant women get.

I tried not to flinch even inwardly, as two ancient Yeoli traditions at once twinged in my bones. She caught me anyway, by the look that flashed across my face, I suppose, and the smile was gone. “Chevenga, what’s wrong with that?”

“Perhaps I’m too superstitious,” I said, “but I won’t think of names again until they both come alive out of the stream.” She just went, “Hrmph.”

I was too ashamed to tell her the other tradition. When the stream-test was stricter, it was all but unheard of for both of a pair of twins to survive it. A Haian would tell you that this is because, having to share a womb, they tend to be born smaller, and there will often be one weak and one strong, so the weak one tends to die. But long ago, when we were a rougher and more ignorant people, it became custom to think of twins as abominations; since so many of them died in the stream, the thinking went, they all ought to. If you read Yeoli history-books, or even tales, from more than five hundred years ago, you find out that if two identical twins lived to grow up, they would rarely stay in their hometown, and would move to places far apart.

Nowadays, twins work and fight and even marry together, holding their heads perfectly high. But, because of the severity of the stream-test my family does, if you look back through the records, you will not find a semanakraseye, either of my family or the other lines that served before, who had a living twin brother or sister. Among some Yeolis, the feeling still holds. I knew Esora-e, who already didn’t like Niku, would ask me if the test had been done properly, if they both lived, and not much favour them.

I didn’t tell Niku this, but I told Kaninjer. Every now and then, I think, he regrets having hired on with someone as barbaric as me, and judging by his look, this was one. But he agreed to give her medicines and put her on a diet that would make the babies grow bigger and stronger.

Since the womb can feel twins are a double burden, it will often bring them forth before it would a singleton, so they’re born with less flesh with which to withstand the teeth of the stream. I’d asked Kaninjer if he could do anything to hold it off, and he said not much; mothers give birth when they give birth, and it would be just as dangerous, or more, if they grew too big within her anyway. Meanwhile I’d sent to Vae Arahi for the stream-testing senaheral, well in advance, to find a stream that was cold enough somewhere in the mountains near the City.

As the time grew closer, I tried to pass off my nervousness as caused by Imperial work, but Niku caught me when I glanced at her enormous belly, and my mother’s andirons flashed into my mind, from when she’d cremated the baby the stream had killed when I was four. “Don’t fear for them, pehali,” she said. “What if they are like Vriah, and can feel every twinge of your emotion?” I fought it off, but that night at the death-hour, when the heart is most laid open to blackness, I felt it so much again I thought I should not sleep beside her, and went to one of the guest-rooms.

The birth itself went without trouble, and they were indeed both boys. If one was weaker than the other, it was not obvious. As she put one to each breast, I fled the room, sick with fear and my mind full of the andirons, calling over my shoulder, “I’m sorry, love, please understand.” When I’d mastered it enough, with the help of Kaninjer’s medicines, I came back. “What’s wrong with you?” she asked me. “I’ve never seen you like this.” I just said something about always being nervous before. I prayed she hadn’t named them in her mind.

When we went up to the place on the second day, the fear for some reason left me, perhaps because I had a task. I had offered to do it if she couldn’t bring herself, but she said, “Anyone else but me doing it would not be honest.” The monks took their places with their feet astride the stream on either side of us and began the song that is the start of the ritual, and she must have made the wall well, for she laid them into the water smoothly enough, one at a time as I held the other, and the upstream monk turned the sandtimer.

I remember the glade with its cypresses straight like spears, under a hot Arkan blue sky, and the tiny ice-cold person in my arms screaming from the depths of his soul. I’d worn my marya with no shirt underneath, which is best, because you can hold them skin to skin. I curled around him, sending love and warmth into him with everything in me, while the second fought his fight. You could see more of me in their eyes, and her in their lips, I’d noticed this morning; their skin was honey brown like hers but more delicately pale, and they had a thin thatch of tiny black curls on the apexes of their heads. Tennunga, I whispered in my mind.

But when the timer ran out and Niku snatched up the second baby, dripping, she did it with a gasp, and her face went pale under her brown skin and flat like the dead. He was not crying and wouldn’t suckle, bad signs. She dashed away into the woods with him, even past the guards, while the monks went on chanting as if she were still there, and I stood not knowing whether to follow her as a husband and a father should, or let her go as if we were having a quarrel. It occurred to me that it might be best for the one I held not to feel what his brother was feeling, so I stayed. By the time she came back, he’d warmed up and his cries were more demanding than death-filled. He wanted her, of course, so we traded again. There would never be warmth for the child I carried back down the rocky path; all I could do was try not to take chill myself from his stiffening body. Now I understood why I’d been so afraid, and why I’d kept seeing the andirons, the last cradle for one whom my mother had foreknown would die.

When we burned him, Niku’s arm curled tenderly as always around Vriah, but her face was as smooth and dry as a wood carving, in the flickering light. It was so unlike her it made me afraid to speak to her; but we must name the one who lived. “It’s by a custom of my people, not yours, that we only have one,” I said. “Let’s name him Rojhai.” Vriah paid no mind at all to what crackled in the fire, utterly fascinated with her little brother in Niku’s sling.

“I won’t name him after my father to relieve my grief,” she said, flatly. “If we named him Rojhai, I would think of this every time we called him. To honour your father would not hurt either of us.”

“I… no. It would be the same the other way, Niku. Let’s name him something else… we can think on it, though we shouldn’t take too long.” A child can’t begin to learn who he is until he’s named, the saying goes. She murmured yes and we were silent again. I felt tears wanting to come, but they wouldn’t while she was dry-eyed. When I held her that night, she was like stone in my arms.

Early the next morning an idea came to me. “We thought we would have two, and so all the love that we, and everyone, would have given two, the one is getting,” I said, over breakfast. She wasn’t eating as much as a mother nursing both a newborn and a toddler should eat, either. The one way she had not been stone was how fiercely she held the newborn precious. “Why don’t we do the same with the names, call him Rojhai Tennunga?”

She agreed. His name is a study in bilingual diction, Rojhai Tennunga aht Niku nar sept Taekun Shae-Arano-e. Everyone calls him Roshten.

Next day, Niku still did not mourn. “Love,” I said, “when Kurkas tortured me, it was silence that was torture, not expression. It was when I was healing that I screamed and wept. You need to let it out.”

“Shrieking and wailing and tearing my hair does nothing,” she said. “It will only make my burden heavier, same for others around me; why would I do that?”

“Are you blaming yourself?”

“I’d be inhuman if I didn’t.”

“But you’re not to blame.”

“I am trying to tell myself that. And that children die… they both could have been stillborn. We know this. It’s not as if I went into it unknowing.”

“If you’re not blaming me, why aren’t you?”

“Omores, it’s not you, it’s your people. I might as well blame the mountains for being themselves, as well blame them as ask for an answer from a voice in the sky, as you say. I’ll say this much: sometimes your ways are shit.”

I’m not helping things, I thought, by not mourning myself. That night I and all my friends in the Elite who’d lost children to the stream got drunk, and I cried on their shoulders.

Sex can break the frozen heart open, of course; and while a woman who’s given birth doesn’t want it for a while, some tender and whole-souled kissing and caressing might move her. I tried the next night, starting with a feather-touch of my tongue on her shoulder, something she usually loved. She went along, but it was as if there were no nerves beneath her skin and no blood in her veins. “I know what you’re doing,” she finally said. “You expected a fiery response from me, and want it one way or another… sometimes they go out, Chevenga. Sometimes you get embers and ashes. You get that when there’s nothing left to burn.”

The heart-slash of grief for the child slowly gave way to the slow bleed of worry for my wife. She began on a memory-tree as the A-niah do, in one of the Marble Palace courtyards, and was out with it even in pouring rain; she also went flying a lot, handing off the children to Baska. My mother sent her a long letter, as did Shaina, Etana and Artira, none of whom she’d met. But she stayed a ghost in human flesh. I’d wake in the dead of night and find her sitting in the dark, as if she were me. After a half-moon, I went to Kaninjer.

He gave her something, and she took it, and then he gave her the same thing higher, and she refused to take another. Alchaen was still in Arko then; his reputation for healing torture was made on having healed mine, and of course there are plenty of people who have suffered it in and around the City. “You recall when your own feeling was locked up, why it was?” he said to me. I thought back, and remembered the sense of being the boy at the city-gates, holding back a horde beyond number outside, with just my lone shoulder. “It’s the same with her. She’s afraid it will be huge beyond imagining and unending, if she allows even a crack.” She would not go to him, saying only, “I’m not crazy.” He told me I’d just have to wait.

I kept wishing I could tell her that if there’s anything life has taught me, it’s to get over one agony as fast as possible so as to be ready for the next. About two moons after Roshten’s birth, Vriah got a throwing-up fever, and nothing Kaninjer could do seemed to keep her from getting sicker. There we’d been expecting to have three children, and now it looked as if they’d be cut down to one. Her weakening only seemed to stop when Kaninjer, not knowing what else to do, stopped giving her the medicine he was most often giving her.

It crashed together in my mind. If you spend enough time with Haians, you pick up a little of their knowledge, especially if you find it fascinating, as I do. Their medicines never have only one use. The one he’d been giving Vriah, because it best matched the sickness she had, was the same one he often gave me, because it best matched my constitution, and neither I nor Krero had ever asked him how he kept his medicine-box secure. He tested the bottle, somehow, and it was indeed slow-poisoned. An assassin who could read a Haian’s notes? “He’d only have to know his medicines,” said Kaninjer. “You’re not that hard to peg.” We never caught him.

Niku didn’t say a word, but just walked stiffly into a parlour off the main chamber, closing the door. Soon came the sounds of things caroming and smashing off the walls. Skorsas flinched at each crash, saying, “Those are priceless antiques.” Her voice took a little longer to find, but in time the cries came too. To me they were like rain in a desert. “But we’ve solved it, the child is going to be fine,” Kaninjer said to me helplessly. “Don’t worry,” I told him. “This is as much or more about the one the stream killed.”

When she came out, her eyes fixed on me like aimed arrowheads, and she grabbed me by the collar and banged me up against a pillar. “I don’t care if I’m a stranger to everyone but one there,” she hissed, her two fists hard under my chin. “You are going to arrange for me and the children you and I both love to live wherever the fik in Yeola-e you come from, and get us out of this stinking cesspit.”

“Good idea, love,” I said. “I surrender and beg mercy.” She had everyone ready to take off in the same time as it took me to write letters to my sister and my mother, and they were gone before cliff-sunset. She and the children never again set foot in Arko until my second term.

So, Niku conceiving again could not be pure joy for us, and there was little to say except to make the calculation. The child would be born next winter, a half-month or so past the solstice, when I was twenty-nine.

--

Friday, March 27, 2009

13 - There would never be warmth for the child

†

†

Posted by

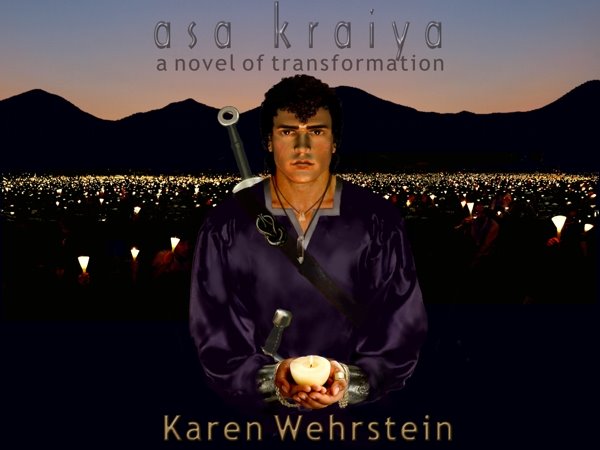

Karen Wehrstein

at

9:19 PM

![]()

![]()