“No mamoka-riding alone” was added to my strictures. “You’re never alone, riding a mamoka!” I protested. “If I tried to jump off his neck, he’d grab me with his nose and put me back on.” Neither Surya, Kaninjer nor any of my spouses believed this, of course, having no experience with mamokal, so the stricture stood; no matter, really, since Alazkaz, the mahu, and I generally took him out together anyway.

The next day, I went before the Committee again, this time with Surya, on the same topic as last time. I hardly said anything; what they had decided to do was ask me to think of each instance, to put myself back in it in time in my mind, and have Surya examine my aura as I did, tell them what he saw and answer their questions. They would gain insight this way that I could not provide myself.

He told them this was best done with the patient lying down, so they brought a couch right into the Committee chamber for me. I was in a trance, breathing deeply and making the white line, pretty much all the way through, not what I’d ever expected in my life to be doing in front of a Committee of Assembly, so I don’t remember it well, only that it seemed like an eternity, and an unusually black and perverse nightmare, except that it was all real. The only mercy was that Surya was there, his hand on my shoulder the whole time.

It went surprisingly fast, actually; I was astonished to see it was barely half-way to noon when we were done. What further insights he gave them, I would not find out for a while; I didn’t do my usual careful perusal of that transcript, until much later. Surya took me straight into his healing room afterwards.

I don’t remember much of the session either, except that there was a lot about acceptance, except one part that stands out vividly, somehow, in my mind, every word etched there. It was after I’d let myself give in to despair, and expressed it. “What am I thinking?” I said, or more exactly whimpered like a baby. “You and they and all Yeola-e and even finally I, the one with the thickest skull, know how fikked in the head I am! What am I doing, why am I bothering, why am I flattering myself to think I can change, why am I not just letting the world be happily rid of me as it would have been?”

He said, “You forget how much you already have changed,” and reminded me. “Think where you would be now, if you had never come to me. Dead, probably, at the hands of that woman and her followers, after doing the Kiss of the Lake. Instead, she is now dead, they are forestalled and so saved, or in healing, and you will probably never do the Kiss of the Lake again.” I lay with my mind boggling and my face itching as the tears dried.

“Remind yourself of that every time you feel you are getting nowhere,” Surya said. “This is the nature of healing. And it is the nature of life, too. Human nature is to want to stay in stasis: to find ease and stay there, to find habits and retain them, even if they are harsh: to remain in the same state of mind. What we pretend not to realize is that there is no such thing as stasis, in truth. We change so ceaselessly that we are change, our lives a cycle, like those of any living creature. We are born, we grow up, we breed, we age, we die; things happen to us and we learn, for good or ill.

“Thus the way of awareness is the way of change, and the greatest sages, both Yeoli and Haian, teach the necessity of always learning, growing within, and healing, all of which are the same thing. For if we don’t get better, we get worse; in our aging, our habits become so graven that they curtail our freedom, and our fortresses become our prisons. I’ve already given you as example, a stark one, as you’d be dead; but that’s more common than you might think.” Engrave these words, I told myself, on your heart.

“I wonder what it is with your shadow-father’s mother,” Surya said to me, same visit. “She’s edged with pain all over, in his aura.”

I told him what I knew, the story that was known in my family. “He left home to marry into the four of my parents, against her will, when he was seventeen. They’ve had no contact since; he wrote several times—including announcing my birth, and all my brothers and sisters—and she never answered, not once, in thirty years. In time he gave up. He’s not willing to try visiting. I don’t blame him; how does he know she’d even open the door?”

“Hmm. His father is barely visible in his aura at all.”

“I don’t think he knew him. His mother raised him single-handed, no shadow-parents. And very strictly, that’s well-known. That’s where he gets it from, himself.”

“What happened to his father?”

“I don’t know, to tell the truth. I gather he abandoned them, though I don’t say that to Esora-e. But I don’t know for sure.”

“You’ve never asked?”

I hadn’t, and hadn’t thought it odd I hadn’t, until now, when it suddenly struck me as very odd. “Well... one knows with Esora-e what not to talk about.”

“It’s odd, that there wouldn’t be a story. Well, perhaps he knows it, but doesn’t tell it. Is she still alive?”

“As far as I know.”

I had a sudden dizzying fear that his next words would be marching orders: “Go and visit her.” But they weren’t. We went on to other things, I don’t recall what.

That night I lay awake thinking, to the sound of my loves’ sleeping breaths. Thirty years, and no letter, no visit; thirty years, and she is family. Something must be done. No one else is planning to do it, so it might as well be me. What I’d feared would be Surya’s orders, I realized I wanted to do on my own inward bidding. I had indeed changed. I slept.

I had to ask a dispensation from the Committee, which they granted more easily than I expected, since I might be gone a good quarter-moon, depending on what happened; I think they were willing because their questioning on suicide had so put me through the grinder. They had other people to speak to, such as Surya himself, and the Haian suicide expert who didn’t know me, Tamenat, who would arrive soon.

I had to ask two dispensations from Surya. I’d be away from him and my spouses, but Krero promised him he’d keep an eye on me, which I knew he’d do assiduously, and so Surya assented. Second, the rough plan I’d conceived involved sparring, though I could do it with wood. He had me tell him again why I wanted to go, so he could inspecting my aura while I said it, then gave me his assent.

Krero wanted to send an escort with me of twenty, no less. “You speak like one whom no Yeoli has ever conspired to kill,” he said, when I protested. He still wore his crystal broken. I thought I had him talked down to four, but then he went to Surya, who concurred with twenty, so twenty it was. Your tax ankaryel at work, if you are Yeoli.

Aside from Surya, I told only Niku and Skorsas why I was going to Chavinel, where Krasila Mangu had always had her war-school, and swore them to silence; for everyone else it was “to central Yeola-e, on consulting business.” I didn’t want my shadow-father to find out unless the results were good, or at least not disastrous.

I sent no letter heralding my visit, but flew in by night, settled my escort in an inn a little out of town, and went to her school the next morning as if I were traveling alone. No brilliance, to guess she was an early riser. Though it was just after dawn, the door was open and I heard the shouts of a class. Being on medical leave, of course, I wasn’t wearing the demarchic signet.

It was a young wristletted class, the oldest students late teens at the most, for which I thanked my luck; older warriors might know me from the war. I had last spoken in Chavinel about nine years ago, so that would help. One student left her place to greet me, very formal and civil. I gave my name as Rao Kyavinara, but named the School of the Sword truthfully, and said I was passing through town, had heard of Krasila’s school and wished to take my day’s exercise here, if that was agreeable. “It is our Teacher’s policy that all such travelers are welcome,” the student said gravely, and waved me to join the line.

I saw the resemblance right away, in the lean, crag-browed elderly woman who led us. The chin, the shape of her arms and hands, a certain stiffness in her walk and her stance, Esora-e had inherited. In her eyes, which were dark brown, I did not see the mean look I had vaguely expected, but her face was definitely hard, and she clearly had spent more time in her life frowning than smiling. Her calling of exercises had precisely the same pace and grimness as Esora-e’s; she need only have a deeper voice and they would be indistinguishable. She paid me no notice.

When it came time for swordwork and everyone else got their true steel, I picked a wooden sword from the rack. That brought Krasila’s attention; she called across the yard offering a loan of steel. I thanked her and said I was using wood alone now for reasons of my own; let her think them spiritual, which was true enough. She seemed suspicious, but I could hardly blame her for sensing some falseness about me.

What I found was what I expected: overlaying all their varied personal styles was a common stiffness, rigidity, hardness, and far too much self-reproach when they made mistakes or were defeated. Though I had come here determined to do no teaching, I could not help but tell them to relax, hold their swords lightly, let the grip be alive and loose in their hands, not stiff and dead, that it wasn’t the end of the world if they missed a parry, just something to learn from, relax and relax and relax some more. They seemed not to believe that they could relax so much and still fight well, for which I had to let myself be living proof; and yet the older ones took it as if they had heard it often from visitors before. I said nothing while Krasila was in earshot.

When we were taking a water-break, one young woman, probably the best I had sparred, came up to me surreptitiously, glancing over her shoulder. “Kere Rao,” she said quietly, “you know how good a person has to be to get into the School of the Sword. Do you think I am?”

“Definitely,” I said. “I can promise you they will hammer you loose, though, tell you much more of the same things I’ve been saying.”

“Oh, I know. And I know I need it, I assure you. You really think I’m good enough?”

“Do I have any reason to lie?”

She glanced over her shoulder again. “No, of course not, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to suggest it... but I have been asking Lady Krasila about it for two years now, and she says I’m not. I will be soon, she keeps saying. But soon never comes.”

Lady Krasila? All-Spirit. “Well, now you have the opinion of one who has sparred every full warrior in the School for fifteen years,” I said. So, she holds the best ones back, I thought, as the student thanked me. Why am I not surprised?

Later in the morning more people came; her under-teachers and their classes, I saw. The game will be up, I thought; some of them were bound to know me from the war. But somehow, by sheer luck, I think, it didn’t come out. There were one or two who stared at me hard, puzzled, but none said anything. I wonder, on retrospect, whether some knew me but said nothing because they thought I was going incognito because of Esora-e. She had taken note of me after all, it seemed, for in the break she gave the students, to have all the teachers spar each other to inspire them, she called me up.

--

Thursday, July 9, 2009

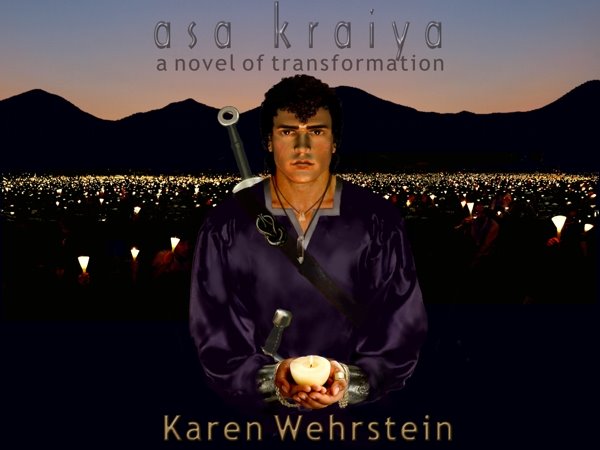

85 - in which I visit my shadow-grandma

†

Posted by

Karen Wehrstein

at

12:54 PM

![]()

![]()