I was up again, as was Krasila, just before dawn. She came sleepily out of her chamber, wearing a fringed robe with lurid pink flowers sewn on all over, and her initial embroidered, all loopy and frilly, in pink satin thread. In my own sleepiness, I must have shown more than I intended, for she drew up and snapped, “What are you staring at? It’s something left over from the occupation.” The last thing a war-teacher wanted to look like, in Arkan-held Yeola-e, was a war-teacher.

I swallowed my witticisms and told her I awaited orders. “Hrmph,” she grumbled as we began making breakfast. “It’s still good, I can get some use out of it, why let it go to waste?”

“He never mentions his father.” I knew she’d know who I meant.

“Just as well. He is a merchant.” She filled the word ‘merchant’ with scorn.

Is, I thought. He is still alive. “Did he never take interest in his son?”

“No. He ran off while I was pregnant.” Knowing? I did not ask.

“Is he in town?”

She laughed. “What, you are going to visit him next? Saddle up your horse... or that flying thing, you did come on one of those chocolate-people’s contraptions, didn’t you? He ran a long way off, like the coward who’s the first to flee and thus start the rout of his comrades, they always get furthest. All the way to Selina. I haven’t heard he’s dead, but perhaps no one would bring me the news.”

I didn’t ask his name, in case she’d refuse to tell it, or lie. Other people in Chavinel, such as my maternal aunts and uncles, would know it.

“Well, I have classes to teach. Will you grace my training-ground with your presence again, semanakraseye Chevenga?” I couldn’t tell whether she was being sarcastic.

“All my regrets,” I said, “I have many things to do. But please, shadow-grandmother, take this to heart: like all family, you are welcome in my house, in Vae Arahi, any time. Our arms are all open to you. When I get home I’ll write, proposing a date.”

Her stare was acidic. “I’ll think about it.”

She let me embrace her as I left, but she was stiff and hard, not bending to it, leaving me feeling as if I’d hugged a spear-shaft. “All my love,” I said as I went. She did not answer.

Esora-e’s father’s name, a cousin of my blood-mother’s told me, was Tyirya Shae-Rilanya-e. The Shae-Rilanya-el told me he was indeed alive and healthy, and gave me his address in Selina. Knowing I’d need them, I’d brought several Vae Arahi pigeons with me; now I sent one home, and to the Committee, asking for forgiveness for my being another half-moon gone, on important business. We took off towards the coast.

In Selina it was hot even a thousand man-heights up. The Miyatara glistened blue beyond the town’s curving shore. Twenty-one wings coming in all at once is cause for a crowd at the landing-field, so in my hooded cloak I hung at the back and let Krero do the talking; “Just military business” was all he said. In the town we split up, he and three others with me, to let me fade into the streets, and he gave me money to buy a gift-flask of wine anonymously.

14th On Cherry Lane was a solid, large, stone house of two storeys. The façade and door were painted bright in the style of harbour-town houses, red-gold with teal trim. I found my heart banging as I tapped.

“Come in, kere!” said a man’s voice, in an inland accent. “It’s open, don’t worry about the dogs.” I tried not to let my mind run ahead of events too fast, imagining what he might be like, but it was very hard. Krasila I had known about, a little, so I had girded myself for a spurning; Tyirya was land uncharted.

The house was painted the same colours inside, open and full of light and flowering plants. It was an office I stepped into, with more than one desk, and leather-bound record-books hanging from pegs, Brahvnikian-style. The man who stood smiling to greet me was the right age, in his sixties and with a spry way of moving. He was bald on top, his hair silver, and his moustache and side-whiskers gave him something of a rakish look. His eyes froze me inside. They were Esora-e’s, precisely.

I’d put my hood back as I came in. “Semanakraseye!” he said. I’d been through this town more than most, and he was the kind who involves himself in worldly affairs, and so would attend speeches. “I... well... Kahara bless us... to what do we owe such an honour? Surely you’ve turned into this door by mistake?” He yelled back into the house, “Donala, bring tea!”

“If this is the house of Tyirya Shae-Rilanya-e,” I said, “it would be the right one.”

“Well! It is. And I am he. Shuretae, no!” A big spotted watch-dog was sticking her nose under my kilt, but backed off on his command. “Please, semanakraseye!” He gestured to the visitor’s chair. “Tea is coming,” he said. “Welcome, all of you!” he said to my escort.

“It’s not a business matter, but personal,” I said.

I had to admire how well he hid his curiosity. “Well, then, come further in, semanakraseye,” he said, drawing me into the parlour. It was warm with dyed sheepskins and hung with art and curios from all over the Miyatara. A second big dog, a brindle, nosed me. I signed Krero and the other three guards to stay in the office, he promised they’d get tea too, and when the door was closed I took a deep breath, trying not to make it noticeable. No excuse not to get to the point. “Tyirya, from what it seems, you do not know I am your shadow-grandson. Is that so?”

He didn’t answer, but the way he seemed to turn into a statue of a man motioning me to a chair made it clear. Either he doesn’t know his son is Esora-e; or he doesn’t know he has a son at all.

“You... me... my... Saint Mother... you my shadow-grandson, how can that be?”

I said, “I think I am going to tell you things which will shock you; should we sip tea for a little, first, or do you want me to get right to it? Perhaps you want a cup of something stronger to hand. For now or later, a gift.” I handed him the flask.

“You are the picture of kindness, semanakraseye,” he said. “As I have always heard.” I could see in his eyes, his mind trying to course the scent, of whom the connection could be, between him and me. “Well... I guess I want you to get right to it. Why wait?”

I said, “When you and Krasila Mangu parted, did you know she was with child?”

He gasped, and I was suddenly afraid his heart might give out. He hadn’t known. In forty-five years, she’d sent him not a word. Something sank in me; I realized that some part of me had wanted him to be uncaring rather than loving. That way I could just have fought with him, rather than wound his soul.

“Mangu!” His voice was barely a croak. “Mangu! Esora-e Mangu! Your shadow-father!” It’s not an uncommon name; he’d thought Esora-e was from a different branch.

“He’s your blood-son.”

“Kahara... oh my Kahara...” He curled up in his chair, face buried in his hands, saying nothing more than that. There was a cabinet that seemed a likely place for cups; I got up and found one, knifed open the flask, filled the cup and put it on the table beside him.

“You are certain? How can you be certain he is my son?”

“I need only see your eyes. The shape of your face, too. Before your hair went grey, was it a very deep brown?”

He signed chalk. His eyes were full of tears when he looked up again, reminding me wrenchingly of Esora-e’s after my father was assassinated. “She didn’t tell me. I swear, Second Fire come if I lie, semanakraseye, she didn’t tell me. Kahara help us all, how could she not? How could she not?”

“Shadow-grandfather, we are family,” I said. “Call me Chevenga. I believe you.”

“I... she... Kahara help me. She... well, kyash.” He leapt to his feet. “This isn’t cause for tears; it’s cause for celebration.” He threw open his arms. “Shadow-grandson. Esora-e Mangu, my son, Fourth Chevenga Shae-Arano-e, my shadow-grandson...! Well, kyash—come here!” I threw open my arms, we thumped together into a hug, and then we were both laughing.

His working day, he said with certainty, was over. Donala turned out to be his daughter, and she and her husband Vira-e went out to cancel the rest of his appointments and gather kin from town. Once the full twenty of my guard were there, as he’d leave none out, he put up the sign marking the office closed. Krero poked around, then pronounced the security impressive enough to meet with his approval; Selina had been occupied for longer than most of Yeola-e.

People were arriving right until dinner hour, at which point Tyirya, his family (including me) and all of my guard but Krero and those on duty were well into our cups. He had forbidden anyone to ask what the connection was between him and me, saying that I should only have to tell it once, over dinner, to everyone, which I did.

After the sun was down and the party had moved out to the yard, Tyirya asked if I’d help him fetch more wine from the cellar, which turned out to be a cunning pretext—it fooled me entirely—to get me away from the party. Since we’d gone inside, it was natural that he should be holding a lit candle; when we went back outside, everyone had one, and was looking at me. I cried helplessly, as always, as they handed me an unlit one. I lit it from his.

When it grew late enough that it would be polite to show me where I would sleep, he did so, an upstairs end-room with a view of the harbour. We stood with cups of nakiti by the window, lit only by moonlight. Something was troubling him, and having several ideas what it might be, I didn’t leave him.

“Chevenga,” he finally asked. “Why is it you here, and not Esora-e himself? I know that Krasila would have taught him that my profession was not worthy of respect; is that it?”

He had told me something of his marriage with her, that had lasted but five years; too decent to decry her, he said only that they’d been incompatible.

I said, “No. He would not despise you for being a merchant; after my father was assassinated they married a sculptor, which he put up with well enough. It’s not that.

“He doesn’t even know I am here. I didn’t even tell him I was going to Chavinel to meet her... in case it went badly. He married my blood parents and his wife against his mother’s will, left home at seventeen to do it. He’s heard not a word from her since, though he wrote her several times. So I thought it best not to tell him where I was going.”

“Not a word... in decades?”

I signed chalk, and told him about how she had kept his room preserved, and the record of his life. A mistake, perhaps; he’d hunger to see it, and she might not let him. I had to rescue those papers.

“I knew she was hard-hearted. I didn’t know she was that hard-hearted. I didn’t think it was possible.” He took a heavy sip of nakiti. “Then she always hid from him who I was, so he never contacted me?”

Here it was; I couldn’t avoid it any longer. “Shadow-grandfather... I cannot be sure, but I think she told him you abandoned her knowing she was with child.”

There was a long silence, in which we heard out-of-tune singing from below, and one of the dogs crunching a bone. Then he flung his cup through the window to smash on the flagstones of the empty street below. So much like Esora-e, that, and then the pacing back and forth like a caged lion.

I won’t commit to paper, what he called her, as it would embarrass him, though I don’t blame him. I will quote this: “I thought she’d ceased to be able to enrage me forty years ago...!” He sat and knotted his hands in his fringe of hair, weeping. “All forty-five years of his life, a child of mine has thought I didn’t want him. Kahara! Aiiigh!”

“Shadow-grandfather,” I said, “he will find out different very soon.” I wrote him, “I’m bringing your father, who loves you,” and sent the pigeon right off the balcony.

Tuesday, July 14, 2009

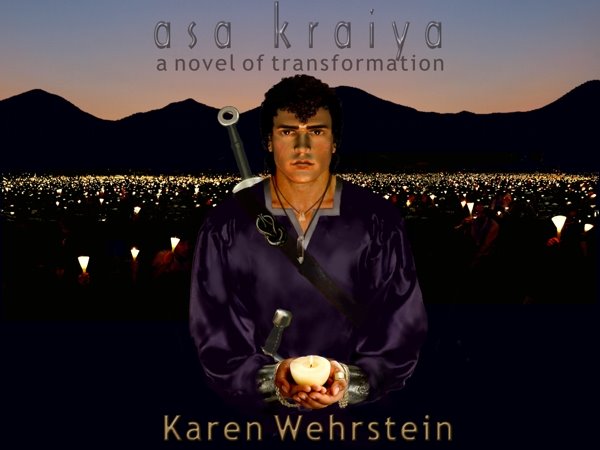

88 - in which I visit my shadow-granddad

†

Posted by

Karen Wehrstein

at

3:07 PM

![]()

![]()