Will people quit calling me that? Virani-e… integrity… a healer’s name… it was like a parody, like a cruel mock, of what I could never imagine even that I could be, so beyond me it was. I was angry as I left Surya’s office; but I had an order to go to the Shrine and so I did. As always, peace seeped in, easing the pangs of frustration. But I felt out of place, like a sword in a library, and as if everyone was staring at me when I wasn’t looking. I went to the main temple, not knowing where else to go, and sat for a time in the great chamber, where a handful of other people prayed or meditated or sat for whatever their reasons were. At least they knew them. My heart was soothed and my spirit expanded as always, but nothing came clear. I realized that a monk asking me what I was doing here was exactly what I did need, and yet I had been being silly when I’d wondered what I’d say if someone asked. No one ever would; the shrine is everyone’s place, after all, no one’s presence questioned. After a while, not knowing what else to do, I got up and went out to stroll through the woods, and look at my favourite stelae as I had when I was a child. I was a little way along when I noticed someone in red was following me. It was Komona. She smiled as I had not seen her smile since I’d first seen her again after the war, like pure clear sun where before there had been a haze of cloud across it. We embraced, and kissed, just a short one. “I didn’t think I’d see you back here so soon,” she said. “Why are you here?” I caught my breath, and thought, I should have known. “Well… my healer sent me.” She waited for more. “But he didn’t know why.” At least she wasn’t the sort of person who’d look at me as if I’d grown a third eye on a stalk on my head when I said that, but just looked thoughtful. “So I know it’s part of my healing, of my going asa kraiya.” “Ah. And so you aren’t sure what to do.” “Well… search out why I am here, I’m thinking. He said perhaps someone here would know, and that I should work my way up the ranks until I found one.” I thought she might laugh at this—hoped for it, perhaps, given the beauty of her laugh—and then ask just what sort of healer this Surya Chaelaecha was. Instead she took my hand again, and said, so seriously it was almost grave, “Let’s skip the intermediary ranks.” † I had never been in the place she took me to, a small flat stone building built part way into the mountainside, though I didn’t know how I could have missed it, being the nosy child I had been. She took me inside to a sparely-furnished office whose feel reminded me of the Benaiat Ivahn’s in Brahvniki, but with blank white walls like Jinai’s auguring room. Behind the desk sat an ancient woman. By the black border of her red robe and the bow Komona offered her, I knew she was one of the great elders of the senaheral. “Esegradaiseye,” Komona said, “you know our semanakraseye.” She didn’t introduce the elder to me, which I guessed must be senahera custom, so that I must address her by the honorific. “One can hardly avoid it,” the esegradaiseye said, with what I tried to tell myself was not sourness. “Fourth Chevenga. We are honoured. Sit.” I understood later, of course, that with a senahera elder, sit just means sit. Her intention was that we sit in silence for a time. Komona, understanding that, bid farewell and was gone. But I felt compelled to explain. “I will tell you the truth, esegradaiseye. I don’t know why I am here. My healer, Surya Chaelaecha, sent me, saying that alone... that he was sending me, I mean, and he didn’t know why. He said it might come clear; else I should try to find someone here who might be able to discern...” She had the sort of eyes that strip you so that you trip over your tongue even if you are being honest, so you end up feeling as if you’re being false; to myself my voice sounded strained. “Well,” I said finally, forcing a laugh, “You know how it is with psyche-healers.” After a pause, she said, “No. I know how it is with All-Spirit, though. And with you: how All-Spirit became but another member of your command council.” I stared at her, her words freezing my tongue to the roof of my mouth, and my back to the chair, as if nailed. While I sat transfixed the esegradaiseye rose delicately, careful of stiff limbs. I could not move. Something told me to close my eyes. She circled me where I sat, slowly, once, examining me from every point. I felt more naked than naked, her eyes seeming to see not only through my clothes, but through my flesh to what is deeper than flesh. Like Surya; but I was used to it from him, had known from the start he was sympathetic. I dared not even breathe, as if she had me open and was probing me with instruments; soon my lungs were straining. As well as all sight, all sound was gone too, except her occasional footstep. “I know why you are here,” she said finally. “I shall have done what must be done.” She opened the door, and was gone. When the door opened next, it was to admit a man monk of about forty, who had very deep-set, sharp-piercing eyes; truth be told he looked like a warrior, his arms hidden beneath his scarlet sleeves, of course, but his wrists thick with muscle and vein-lined. I wondered if he was asa kraiya, and made up my mind to ask him, if the right chance came. But I felt as if I were in a ceremony already, and so said nothing. “Semanakraseye,” he said, and beckoned me to follow. There were two younger monks with him, also men, who said nothing; one carried a wooden box under his arm. They fell into step behind me. We went down to Terera, where the spring air was balmy, and everything had burst out green, all the trees well in leaf. On the edge of town, the oldest asked me, “Have you had dinner?” When I told him no, we became a party of four like any other, each speaking his preferences until we came to a consensus on which restaurant (Kyara’s, as it turned out). But oddness intruded again when we were done eating and they were about to pay; the oldest monk put his hand on my shoulder, and said, “You haven’t availed yourself of the privy here. Do so.” Just as if I were five and he were my mother, except for the formal tone; I guess I was in some way shrunk down to five again, for I obeyed him without question. He also made sure I finished my cup of water. On the doorstep as we were leaving, he stopped me by a hand on the shoulder again. “You may not see where we take you,” he said, blindfolded me with a black kerchief, and gave me his elbow. Thus, of course, I don’t know where we went. By the sounds and smells and feel of the air, I could tell we walked a while through farmland, and then entered forest. My sight taken from me, and all of us silent as we walked, I found my other senses became keener. Life rising and opening to the sun, like a woman’s precious parts opening to the caress of a warm tongue, I suddenly found I was feeling, as a force almost pressing on my skin, warm and green, honeyed with the scent of flowers, jewelled with the minute songs of birds and insects. The earth seemed to slowly surge and unfurl, teeming, under my feet. Even the monk’s arm-muscle in my fingers, from which, as blind people know, I quickly learned to feel where he was going to go, seemed astonishingly alive. We came to what I sensed was a clearing, and he and I stopped as one, and he told me to strip naked and sit. I heard the younger monks open the box. Then all three of them chanted an invocation to All-Spirit, and did some other ceremony in a circle around me. The soft spring air, slightly freshened with the falling of the sun, stroked the places on my skin that were sensitive for being usually covered. “Semanakraseye,” said the oldest monk, “to undergo what you are about to requires that you be deprived of those senses we can extend outward beyond our body. You are already blindfolded, and we will stop your ears; but you in particular have one other. The esegradaiseye said you carry with you the means to take it from you.” I took a deep breath, swallowed a sudden dryness. Sometimes it is terrifying, to learn just how much detail monks and healers and great war-masters can see about us. “Yes,” I said, hearing my own words as if from outside myself. “In my pouch, in the front pocket, you will find a fine brass chain. While I wear that around my neck I am without that other sense.” They put it on me. Since no one near was armed, nothing felt different; but knowing it wouldn’t even if the front rank of an army marched into this clearing with spears levelled, I felt more deeply blinded than any dark cloth could make me. “Drink.” He made me take another long draught of water. “Lie down, and spread your limbs wide.” I did, and the mallet-blows, as they drove the stakes deep into the earth, I felt through it like blows to a numb part. They bound my wrists and ankles softly, but too securely to move at all. I found myself having to control my breathing, keeping it slow and deep, already. The oldest monk laid his hand on my forehead. “Semanakraseye.” This time, he intoned my title as if invoking me, and the rest of his words had the ritual cadence. “When a person comes to the senaheral, a sacrifice is asked of him, that is the most difficult thing for him; he must enter that which is hardest for him, which is where his greatest learning lies. In your case, the esegradaiseye saw that the sacrifice must be power, that you must enter helplessness, for it is there that your greatest and richest mysteries wait. “We will return to free you when it is finished.” He pressed the plugs, which were of waxed felt, I think, deep into my ears, snuffing the song of the woods to silence. Through the earth I felt their footsteps recede. --

Monday, August 17, 2009

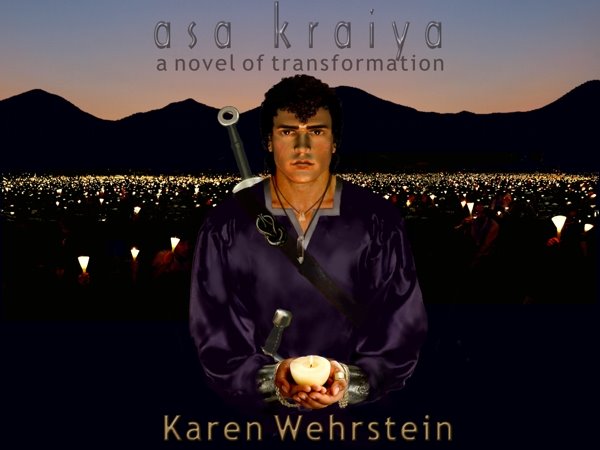

109 - Where his greatest learning lies

Posted by

Karen Wehrstein

at

7:56 PM

![]()

![]()